In environments that run Active Directory (AD), Kerberos issues “tickets” that prove who you are and what you can access. Services validate those tickets when deciding whether to let users in. When that verification flow stays trustworthy, access remains predictable and auditable.

A silver ticket attack exploits how certain services accept tickets, allowing quiet access to specific resources with minimal domain controller noise. This article explains how silver ticket attacks work, and discusses how to detect and prevent them across your AD environment.

What Is a Silver Ticket Attack?

A silver ticket is a forged Kerberos service ticket. An attacker who has a service account’s secret, often its new technology LAN manager (NTLM) hash or advanced encryption standard (AES) key, can mint a valid-looking ticket-granting service (TGS) offline and sign it with the stolen secret. Then they’ll present that TGS to the target service tied to the relevant service principal name (SPN), such as HTTP or SQL, with no domain controller interaction needed.

A silver ticket attack uses that forged TGS to gain stealthy, service-scoped access. It doesn’t unlock the whole domain in the same way a golden ticket attack does, and it often slips past monitoring because the domain controller never logs a matching TGS request—most traces live on the targeted host.

With many critical services, that “just enough access” is sufficient to allow for lateral movement and further credential theft. This is considered an identity-based attack, because the attacker abuses trusted credentials to convince a service they're legitimate.

How Silver Ticket Attacks Work

Here's how a typical silver ticket attack plays out in AD, after initial access via phishing, malware, or an exposed service:

- Pick a service to impersonate: The attacker targets something useful, like the Common Internet File System (CIFS) or Microsoft SQL Server (MSSQL), and notes the exact SPN and domain information the forged ticket must match.

- Get the service account secret: Next the attacker pulls credential information for that account, often as an NTLM hash in environments using RC4 encryption, or an AES key in modern environments that enforce AES-only Kerberos. Common paths include credential dumping after a local-admin foothold or cracking the service account via Kerberoasting to obtain the secret.

- Forge the Kerberos service ticket offline: With that secret, the attacker generates a look-alike TGS for the chosen SPN, sets identity fields that blend in, chooses an accepted encryption type, and signs it so the target will accept the ticket. Hackers often use tools like Mimikatz during this step to aid in ticket creation.

- Inject the ticket and authenticate to the service: Next, the attacker inserts the forged ticket into a session and authenticates to the host or application. No TGS request touches the DC, so DC-side telemetry stays quiet while the service treats the ticket as valid.

- Work inside the service’s scope: With their new access, the attacker can read data and run actions. They can also achieve privilege escalation, especially if the attacker carries over permissive rights and the environment lacks correlated logging.

How to Detect a Silver Ticket Attack

If a Kerberos silver ticket attack is in play, your domain controller may stay quiet. But you can still detect the attack by following these indicators and correlating them across hosts and the DC:

- Service/DC mismatch: You see a successful logon on the target host (for example, Event ID 4624), but there’s no preceding TGT request in the domain controller (no event ID 4768 for that access). This gap is a common silver ticket pattern, because the forged service ticket never goes through the DC.

- Ticket metadata anomalies: Tickets accepted by the service show odd details such as encryption types that contradict policy, lifetimes that don’t line up, or privilege attribute certificates that look wrong.

- SPN or realm inconsistencies: The service receives a ticket with an SPN that doesn't match the resource being accessed, or with a realm (the Kerberos authentication domain, such as MYORG.COM in AD) that doesn't align with the service's expected domain/realm. This happens because attackers sometimes set incorrect SPN or realm values in these fields when forging tickets.

- Abnormal service behavior: You see repeated authentications to high-value services from unusual sources and sparse DC telemetry.

How to Prevent a Silver Ticket Attack

Silver tickets are tough to block outright, because they abuse the normal Kerberos behavior in AD. However, putting these controls in place helps service account secrets stay out of reach and short-lived.

Enforce Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA)

Require MFA anywhere an attacker could elevate or touch service identities—including domain admins, tier-0 systems, identity tooling, and servers that manage service configuration. MFA won’t neutralize a forged ticket, but it raises the bar for the initial compromise paths that usually reveal service account secrets.

Use Strong Account Secrets

Most service accounts rely on long, random passwords from which the NTLM hash and AES keys used to sign tickets are derived. Use group managed service accounts (gMSA) wherever supported—Windows generates 240-byte passwords and rotates them automatically every 30 days.

If gMSA isn’t an option, store a long, random password in a vault, rotate it on a tight schedule, and never reuse it across hosts. In Kerberos, a password hash equals the password, so treat these credentials as high-value secrets.

Apply the Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP)

Grant only the permissions each account needs to run its service. Remove local admin and broad directory privileges, limit SPNs to required services, and bind accounts to the hosts they use. With PoLP in place, a forged ticket has less reach, reducing lateral movement.

Tighten Your Kerberos Policy Hygiene

Force modern encryption and shorten the window of misuse. Set services and domain policy to AES-only, and retire RCA and NTLM where possible. And thoroughly test RC4 retirement in a staging environment first—legacy systems may fail authentication until you update or reconfigure them.

You should also tune ticket lifetimes and renewal periods to match policy—the default service ticket lifetime is 600 minutes (10 hours)—and then watch for tickets outside those bounds. These settings make a forged ticket harder to build in a format your services will accept and easier to spot when someone tries.

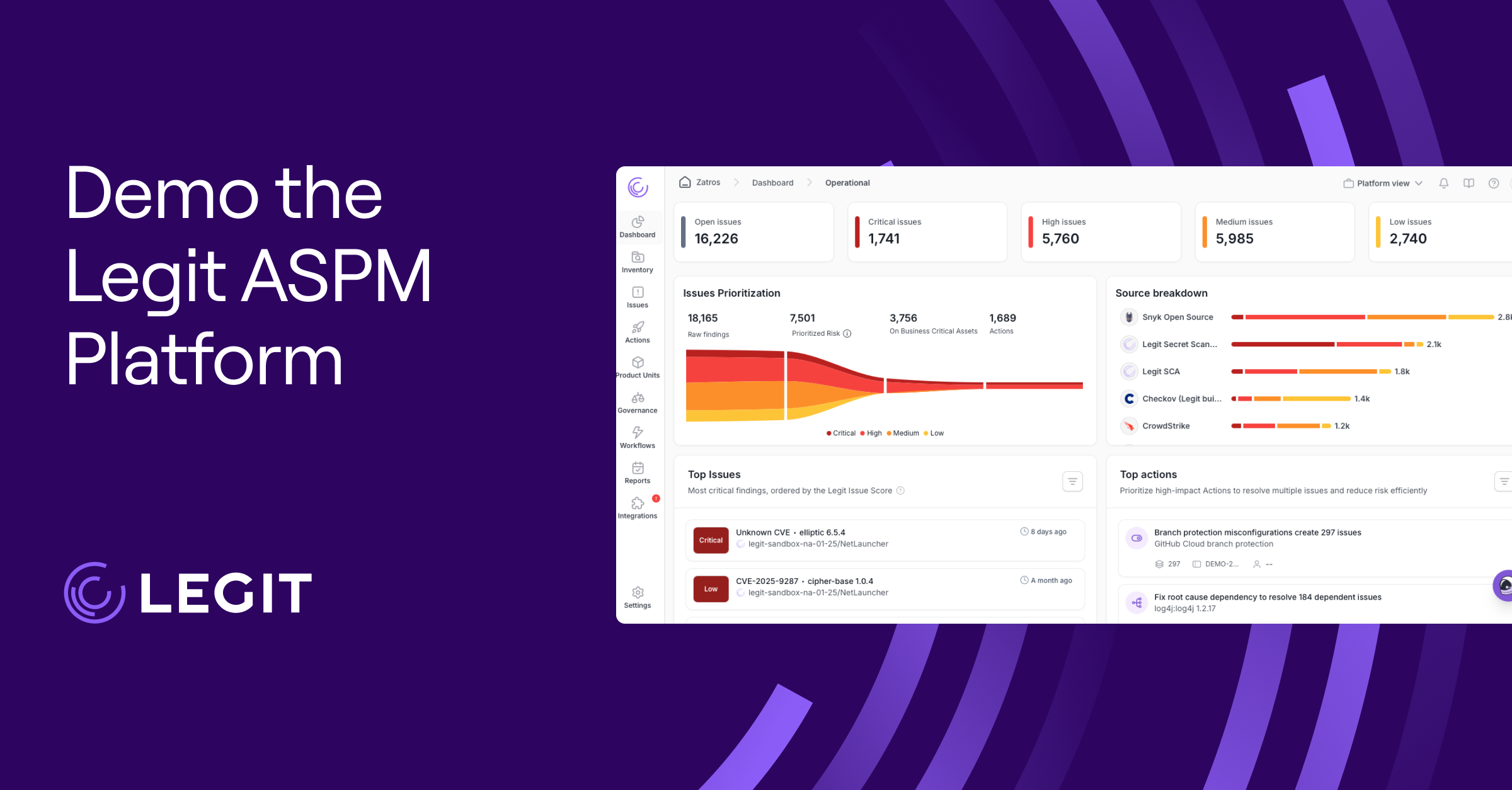

Reduce Silver Ticket Attack Risk With Legit Security

Silver tickets feed on long-lived service secrets and configuration drift. These issues often start in development when credentials land in code or jobs, scripts run with broad rights, or policy checks never reach pull requests.

Legit closes that gap by securing your software supply chain and developer environments. You get enterprise-grade secrets scanning in repos and pipelines, policy checks in pull requests and continuous integration, and unified remediation that routes fixes to the right owners. This combination lowers the chance that a service account secret will leak, shortens the access window if one does, and limits how far a forged ticket can go.

Request a demo today to secure your code, pipelines, and developer tools with Legit.

Download our new whitepaper.